We must face our fears if we want to get the most out of technology — and we must conquer those fears if we want to get the best out of humanity, says Garry Kasparov. One of the greatest chess players in history, Kasparov lost a memorable match to IBM supercomputer Deep Blue in 1997. Now he shares his vision for a future where intelligent machines help us turn our grandest dreams into reality.

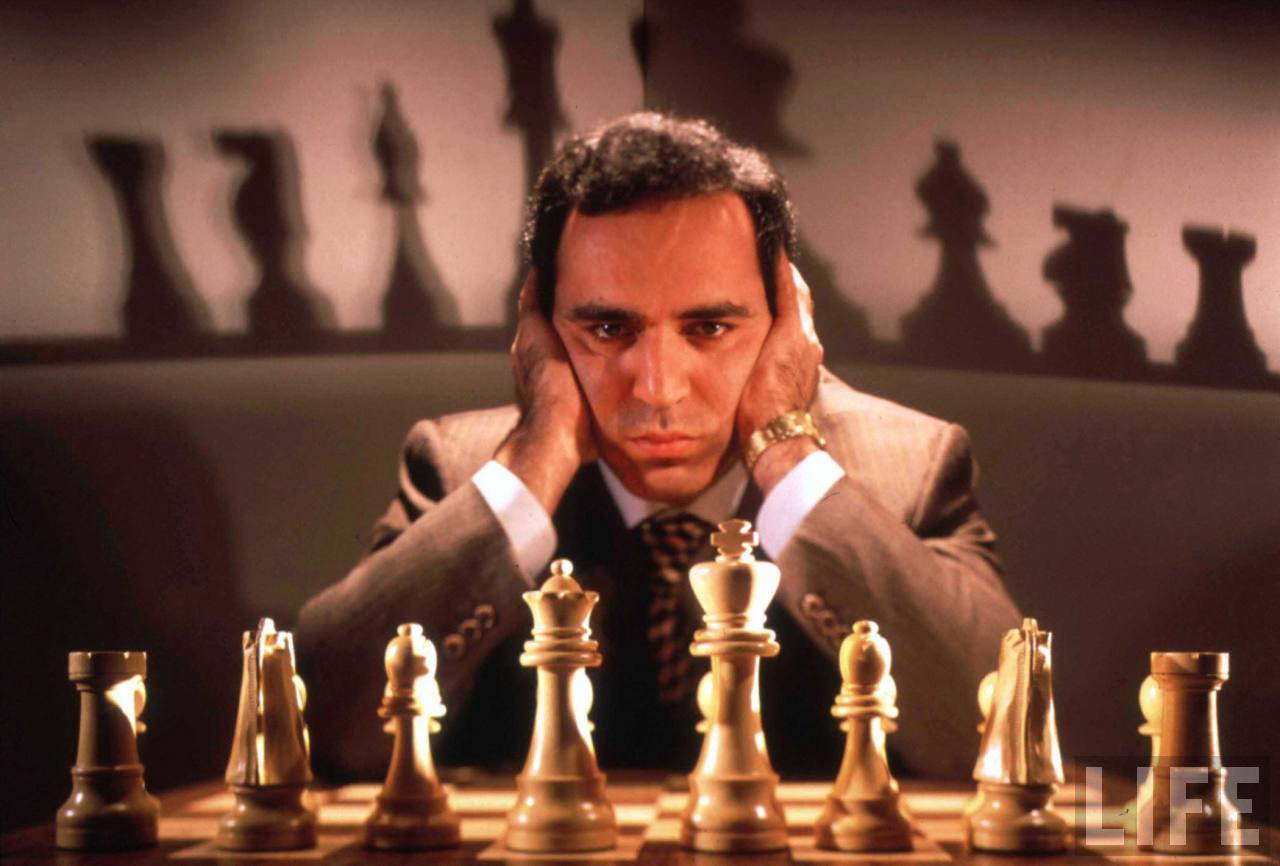

This story begins in 1985 when at age 22, I became the World Chess Champion after beating Anatoly Karpov. Earlier that year, I played what is called a simultaneous exhibition against 32 of the world’s best chess-playing machines in Hamburg, Germany. I won all the games, and then it was not considered much of a surprise that I could beat 32 computers at the same time. To me, that was the golden age.

Just 12 years later, I was fighting for my life against just one computer in a match called by the cover of “Newsweek” “The Brain’s Last Stand.” No pressure.

From mythology to science fiction, the human versus machine has been often portrayed as a matter of life and death. John Henry, called the steel-driving man in the 19th century African American folk legend, was pitted in a race against a steam-powered hammer bashing a tunnel through mountain rock. John Henry’s legend is a part of a long historical narrative pitting humanity versus technology. And this competitive rhetoric is standard now. We are in a race against the machines, in a fight, or even in a war. Jobs are being killed off. People are being replaced as if they had vanished from the Earth. It’s enough to think that the movies like “The Terminator” or “The Matrix” are nonfiction.

There are very few instances of an arena where the human body and mind can compete on equal terms with a computer or a robot. Actually, I wish there were a few more. Instead, it was my blessing and my curse to literally become the proverbial man in the man versus machine competition that everybody is still talking about. In the most famous human-machine competition since John Henry, I played two matches against the IBM supercomputer, Deep Blue. Nobody remembers that I won the first match —

In Philadelphia, before losing the rematch the following year in New York. But I guess that’s fair. There is no day in history, a special calendar entry for all the people who failed to climb Mt. Everest before Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay made it to the top. And in 1997, I was still the world champion when chess computers finally came of age. I was Mt. Everest, and Deep Blue reached the summit. I should say of course, not that Deep Blue did it, but its human creators — Anantharaman, Campbell, Hoane, Hsu. Hats off to them. As always, the machine’s triumph was a human triumph, something we tend to forget when humans are surpassed by our own creations.

Deep Blue was victorious, but was it intelligent? No, no it wasn’t, at least not in the way Alan Turing and other founders of computer science had hoped. It turned out that chess could be crunched by brute force, once hardware got fast enough and algorithms got smart enough. Although by the definition of the output, grandmaster-level chess, Deep Blue was intelligent. But even at the incredible speed, 200 million positions per second, Deep Blue’s method provided little of the dreamed-of insight into the mysteries of human intelligence.

Soon, machines will be taxi drivers and doctors and professors, but will they be “intelligent?” I would rather leave these definitions to the philosophers and to the dictionary. What really matters is how we humans feel about living and working with these machines.

When I first met Deep Blue in 1996 in February, I had been the world champion for more than 10 years, and I had played 182 world championship games and hundreds of games against other top players in other competitions. I knew what to expect from my opponents and what to expect from myself. I was used to measuring their moves and gauging their emotional state by watching their body language and looking into their eyes.

And then I sat across the chessboard from Deep Blue. I immediately sensed something new, something unsettling. You might experience a similar feeling the first time you ride in a driverless car or the first time your new computer manager issues an order at work. But when I sat at that first game, I couldn’t be sure what is this thing capable of. Technology can advance in leaps, and IBM had invested heavily. I lost that game. And I couldn’t help wondering, might it be invincible? Was my beloved game of chess over? These were human doubts, human fears, and the only thing I knew for sure was that my opponent Deep Blue had no such worries at all.

I fought back after this devastating blow to win the first match, but the writing was on the wall. I eventually lost to the machine but I didn’t suffer the fate of John Henry who won but died with his hammer in his hand. It turned out that the world of chess still wanted to have a human chess champion. And even today, when a free chess app on the latest mobile phone is stronger than Deep Blue, people are still playing chess, even more than ever before. Doomsayers predicted that nobody would touch the game that could be conquered by the machine, and they were wrong, proven wrong, but doomsaying has always been a popular pastime when it comes to technology.

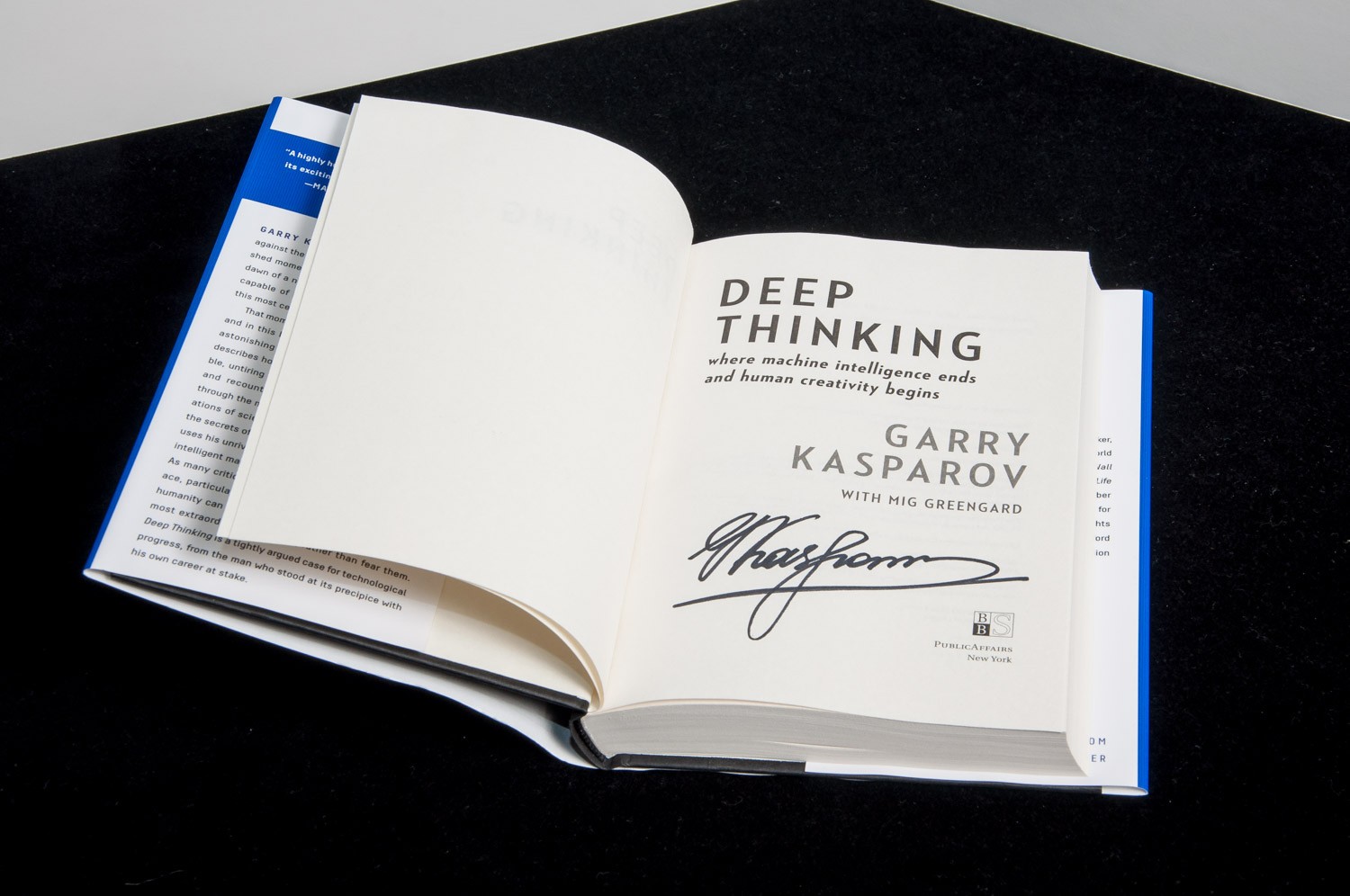

What I learned from my own experience is that we must face our fears if we want to get the most out of our technology, and we must conquer those fears if we want to get the best out of our humanity. While licking my wounds, I got a lot of inspiration from my battles against Deep Blue. As the old Russian saying goes, if you can’t beat them, join them. Then I thought, what if I could play with a computer — together with a computer at my side, combining our strengths, human intuition plus machine’s calculation, human strategy, machine tactics, human experience, machine’s memory. Could it be the perfect game ever played?

My idea came to life in 1998 under the name of Advanced Chess when I played this human-plus-machine competition against another elite player. But in this first experiment, we both failed to combine human and machine skills effectively. Advanced Chess found its home on the internet, and in 2005, a so-called freestyle chess tournament produced a revelation. A team of grandmasters and top machines participated, but the winners were not grandmasters, not a supercomputer. The winners were a pair of amateur American chess players operating three ordinary PCs at the same time. Their skill of coaching their machines effectively counteracted the superior chess knowledge of their grandmaster opponents and much greater computational power of others. And I reached this formulation. A weak human player plus a machine plus a better process is superior to a very powerful machine alone, but more remarkably, is superior to a strong human player plus a machine and an inferior process. This convinced me that we would need better interfaces to help us coach our machines towards more useful intelligence.

The human plus machine isn’t the future, it’s the present. Everybody that’s used online translation to get the gist of a news article from a foreign newspaper, knowing it’s far from perfect. Then we use our human experience to make sense out of that, and then the machine learns from our corrections. This model is spreading and investing in medical diagnosis, security analysis. The machine crunches data, calculates probabilities, gets 80 percent of the way, 90 percent, making it easier for analysis and decision-making of the human party. But you are not going to send your kids to school in a self-driving car with 90 percent accuracy, even with 99 percent. So we need a leap forward to add a few more crucial decimal places.

Twenty years after my match with Deep Blue, second match, this sensational “The Brain’s Last Stand” headline has become commonplace as intelligent machines move in every sector, seemingly every day. But unlike in the past, when machines replaced farm animals, manual labor, now they are coming after people with college degrees and political influence. And as someone who fought machines and lost, I am here to tell you this is excellent, excellent news. Eventually, every profession will have to feel these pressures, or else it will mean humanity has ceased to make progress. We don’t get to choose when and where technological progress stops. We cannot slow down. In fact, we have to speed up. Our technology excels at removing difficulties and uncertainties from our lives, and so we must seek out ever more difficult, ever more uncertain challenges.

Machines have calculations. We have understanding. Machines have instructions. We have a purpose. Machines have objectivity. We have passion. We should not worry about what our machines can do today. Instead, we should worry about what they still cannot do today, because we will need the help of the new, intelligent machines to turn our grandest dreams into reality. And if we fail, if we fail, it’s not because our machines are too intelligent, or not intelligent enough. If we fail, it’s because we grew complacent and limited our ambitions. Our humanity is not defined by any skill, like swinging a hammer or even playing chess.

There’s one thing only a human can do. That’s a dream. So let us dream big.