Would you like to watch an Informative Documentary on Artificial Intelligence And Robotics recorded recently ?

Computers can already solve problems in limited realms. The basic idea of AI problem-solving is very simple, though its execution is complicated. First, the AI robot or computer gathers facts about a situation through sensors or human input. The computer compares this information to stored data and decides what the information signifies. The computer runs through various possible actions and predicts which action will be most successful based on the collected information. Of course, the computer can only solve problems it’s programmed to solve — it doesn’t have any generalized analytical ability. Chess computers are one example of this sort of machine.

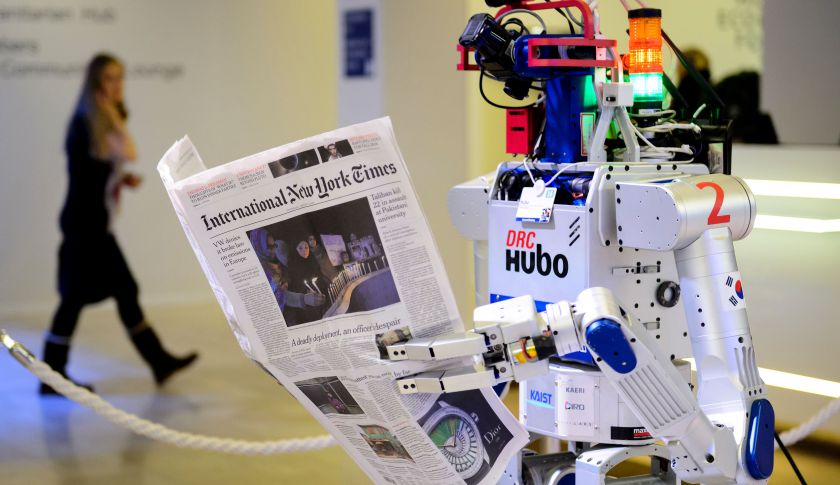

Some modern robots also have the ability to learn in a limited capacity. Learning robots recognize if a certain action (moving its legs in a certain way, for instance) achieved a desired result (navigating an obstacle). The robot stores this information and attempts the successful action the next time it encounters the same situation. Again, modern computers can only do this in very limited situations. They can’t absorb any sort of information like a human can. Some robots can learn by mimicking human actions. In Japan, roboticists have taught a robot to dance by demonstrating the moves themselves.

Some robots can interact socially. Kismet, a robot at M.I.T’s Artificial Intelligence Lab, recognizes human body language and voice inflection and responds appropriately. Kismet’s creators are interested in how humans and babies interact, based only on tone of speech and visual cue. This low-level interaction could be the foundation of a human-like learning system.

Kismet and other humanoid robots at the M.I.T. AI Lab operate using an unconventional control structure. Instead of directing every action using a central computer, the robots control lower-level actions with lower-level computers. The program’s director, Rodney Brooks, believes this is a more accurate model of human intelligence. We do most things automatically; we don’t decide to do them at the highest level of consciousness.

The real challenge of AI is to understand how natural intelligence works. Developing AI isn’t like building an artificial heart — scientists don’t have a simple, concrete model to work from. We do know that the brain contains billions and billions of neurons, and that we think and learn by establishing electrical connections between different neurons. But we don’t know exactly how all of these connections add up to higher reasoning, or even low-level operations. The complex circuitry seems incomprehensible.

Because of this, AI research is largely theoretical. Scientists hypothesize on how and why we learn and think, and they experiment with their ideas using robots. Brooks and his team focus on humanoid robots because they feel that being able to experience the world like a human is essential to developing human-like intelligence. It also makes it easier for people to interact with the robots, which potentially makes it easier for the robot to learn.

Just as physical robotic design is a handy tool for understanding animal and human anatomy, AI research is useful for understanding how natural intelligence works. For some roboticists, this insight is the ultimate goal of designing robots. Others envision a world where we live side by side with intelligent machines and use a variety of lesser robots for manual labor, health care and communication. A number of robotics experts predict that robotic evolution will ultimately turn us into cyborgs — humans integrated with machines. Conceivably, people in the future could load their minds into a sturdy robot and live for thousands of years!

In any case, robots will certainly play a larger role in our daily lives in the future. In the coming decades, robots will gradually move out of the industrial and scientific worlds and into daily life, in the same way that computers spread to the home in the 1980s.

http://science.howstuffworks.com/robot6.htm