Meet the “Row-bot,” a robot that cleans up pollution and generates the electricity needed to power itself by swallowing dirty water. Roboticist Jonathan Rossiter explains how this special swimming machine, which uses a microbial fuel cell to neutralize algal blooms and oil slicks, could be a precursor to biodegradable, autonomous pollution-fighting robots.

“I’m an engineer and I make robots. Now, of course you all know what a robot is, right? If you don’t, you’d probably go to Google, and you’d ask Google what a robot is. So let’s do that. We’ll go to Google and this is what we get. Now, you can see here there are lots of different types of robots, but they’re predominantly humanoid in structure. And they look pretty conventional because they’ve got plastic, they’ve got metal, they’ve got motors and gears and so on. Some of them look quite friendly, and you could go up and you could hug them. Some of them not so friendly, they look like they’re straight out of “Terminator,” in fact they may well be straight out of “Terminator.” You can do lots of really cool things with these robots — you can do really exciting stuff.

But I’d like to look at different kinds of robots — I want to make different kinds of robots. And I take inspiration from the things that don’t look like us, but look like these. So these are natural biological organisms and they do some really cool things that we can’t, and current robots can’t either. They do all sorts of great things like moving around on the floor; they go into our gardens and they eat our crops;they climb trees; they go in water, they come out of water; they trap insects and digest them. So they do really interesting things. They live, they breathe, they die, they eat things from the environment. Our current robots don’t really do that. Now, wouldn’t it be great if you could use some of those characteristics in future robots so that you could solve some really interesting problems? I’m going to look at a couple of problems now in the environment where we can use the skills and the technologies derived from these animals and from the plants, and we can use them to solve those problems.

Let’s have a look at two environmental problems. They’re both of our making — this is man interacting with the environment and doing some rather unpleasant things. The first one is to do with the pressure of population. Such is the pressure of population around the world that agriculture and farming is required to produce more and more crops. Now, to do that, farmers put more and more chemicals onto the land.They put on fertilizers, nitrates, pesticides — all sorts of things that encourage the growth of the crops,but there are some negative impacts. One of the negative impacts is if you put lots of fertilizer on the land, not all of it goes into the crops. Lots of it stays in the soil, and then when it rains, these chemicals go into the water table. And in the water table, then they go into streams, into lakes, into rivers and into the sea. Now, if you put all of these chemicals, these nitrates, into those kinds of environments, there are organisms in those environments that will be affected by that — algae, for example. Algae loves nitrates, it loves fertilizer, so it will take in all these chemicals, and if the conditions are right, it will mass produce.It will produce masses and masses of new algae. That’s called a bloom. The trouble is that when algae reproduces like this, it starves the water of oxygen. As soon as you do that, the other organisms in the water can’t survive. So, what do we do? We try to produce a robot that will eat the algae, consume it and make it safe.

So that’s the first problem. The second problem is also of our making, and it’s to do with oil pollution.Now, oil comes out of the engines that we use, the boats that we use. Sometimes tankers flush their oil tanks into the sea, so oil is released into the sea that way. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could treat that in some way using robots that could eat the pollution the oil fields have produced? So that’s what we do.We make robots that will eat pollution.

To actually make the robot, we take inspiration from two organisms. On the right there you see the basking shark. The basking shark is a massive shark. It’s noncarnivorous, so you can swim with it, as you can see. And the basking shark opens its mouth, and it swims through the water, collecting plankton. As it does that, it digests the food, and then it uses that energy in its body to keep moving. So, could we make a robot like that — like the basking shark that chugs through the water and eats up pollution? Well, let’s see if we can do that. But also, we take the inspiration from other organisms. I’ve got a picture here of a water boatman, and the water boatman is really cute. When it’s swimming in the water, it uses its paddle-like legs to push itself forward.

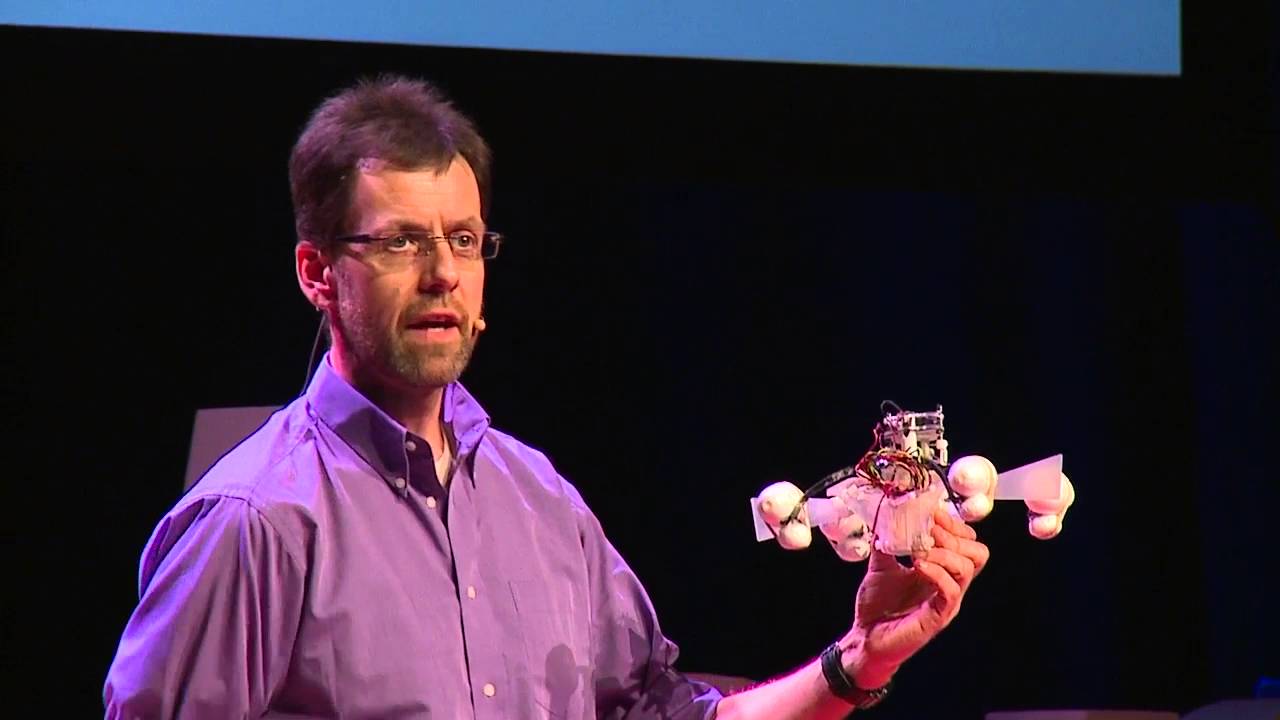

So we take those two organisms and we combine them together to make a new kind of robot. In fact, because we’re using the water boatman as inspiration, and our robot sits on top of the water, and it rows,we call it the “Row-bot.” So a Row-bot is a robot that rows. OK. So what does it look like? Here’s some pictures of the Row-bot, and you’ll see, it doesn’t look anything like the robots we saw right at the beginning. Google is wrong; robots don’t look like that, they look like this.

So I’ve got the Row-bot here. I’ll just hold it up for you. It gives you a sense of the scale, and it doesn’t look anything like the others. OK, so it’s made out of plastic, and we’ll have a look now at the components that make up the Row-bot — what makes it really special.

The Row-bot is made up of three parts, and those three parts are really like the parts of any organism. It’s got a brain, it’s got a body and it’s got a stomach. It needs the stomach to create the energy. Any Row-bot will have those three components, and any organism will have those three components, so let’s go through them one at a time. It has a body, and its body is made out of plastic, and it sits on top of the water. And it’s got flippers on the side here — paddles that help it move, just like the water boatman. It’s got a plastic body, but it’s got a soft rubber mouth here, and a mouth here — it’s got two mouths. Why does it have two mouths? One is to let the food go in and the other is to let the food go out. So you can see really it’s got a mouth and a derriere, or a —something where the stuff comes out, which is just like a real organism. So it’s starting to look like that basking shark. So that’s the body.

The second component might be the stomach. We need to get the energy into the robot and we need to treat the pollution, so the pollution goes in, and it will do something. It’s got a cell in the middle here called a microbial fuel cell. I’ll put this down, and I’ll lift up the fuel cell. Here. So instead of having batteries, instead of having a conventional power system, it’s got one of these. This is its stomach. And it really is a stomach because you can put energy in this side in the form of pollution, and it creates electricity.

So what is it? It’s called a microbial fuel cell. It’s a little bit like a chemical fuel cell, which you might have come across in school, or you might’ve seen in the news. Chemical fuel cells take hydrogen and oxygen,and they can combine them together and you get electricity. That’s well-established technology; it was in the Apollo space missions. That’s from 40, 50 years ago. This is slightly newer. This is a microbial fuel cell. It’s the same principle: it’s got oxygen on one side, but instead of having hydrogen on the other, it’s got some soup, and inside that soup there are living microbes. Now, if you take some organic material —could be some waste products, some food, maybe a bit of your sandwich — you put it in there, the microbes will eat that food, and they will turn it into electricity. Not only that, but if you select the right kind of microbes, you can use the microbial fuel cell to treat some of the pollution. If you choose the right microbes, the microbes will eat the algae. If you use other kinds of microbes, they will eat petroleum spirits and crude oil. So you can see how this stomach could be used to not only treat the pollution but also to generate electricity from the pollution. So the robot will move through the environment, taking food into its stomach, digest the food, create electricity, use that electricity to move through the environment and keep doing this.

Let’s see what happens when we run the Row-bot — when it does some rowing. Here we’ve got a couple of videos, the first thing you’ll see — hopefully you can see here is the mouth open. The front mouth and the bottom mouth open, and it will stay opened enough, then the robot will start to row forward. It moves through the water so that food goes in as the waste products go out. Once it’s moved enough, it stops and then it closes the mouth — slowly closes the mouths — and then it will sit there, and it will digest the food.

Of course these microbial fuel cells, they contain microbes. What you really want is lots of energy coming out of those microbes as quickly as possible. But we can’t force the microbes and they generate a small amount of electricity per second. They generate milliwatts, or microwatts. Let’s put that into context.Your mobile phone for example, one of these modern ones, if you use it, it takes about one watt. So that’s a thousand or a million times as much energy that that uses compared to the microbial fuel cell.How can we cope with that? Well, when the Row-bot has done its digestion, when it’s taken the food in,it will sit there and it will wait until it has consumed all that food. That could take some hours, it could take some days. A typical cycle for the Row-bot looks like this: you open your mouth, you move, you close your mouth and you sit there for a while waiting. Once you digest your food, then you can go about doing the same thing again. But you know what, that looks like a real organism, doesn’t it? It looks like the kind of thing we do. Saturday night, we go out, open our mouths, fill our stomachs, sit in front of the telly and digest. When we’ve had enough, we do the same thing again.

If we’re lucky with this cycle, at the end of the cycle we’ll have enough energy left over for us to be able to do something else. We could send a message, for example. We could send a message saying,“This is how much pollution I’ve eaten recently,” or, “This is the kind of stuff that I’ve encountered,” or, “This is where I am.” That ability to send a message saying, “This is where I am,” is really, really important. If you think about the oil slicks that we saw before, or those massive algal blooms, what you really want to do is put your Row-bot out there, and it eats up all of those pollutions, and then you have to go collect them. Why? Because these Row-bots at the moment, this Row-bot I’ve got here, it contains motors, it contains wires, it contains components which themselves are not biodegradable. Current Row-bots contain things like toxic batteries. You can’t leave those in the environment, so you need to track them, and then when they’ve finished their job of work, you need to collect them. That limits the number of Row-bots you can use. If, on the other hand, you have robot a little bit like a biological organism, when it comes to the end of its life, it dies and it degrades to nothing.

So wouldn’t it be nice if these robots, instead of being like this, made out of plastic, were made out of other materials, which when you throw them out there, they biodegrade to nothing? That changes the way in which we use robots. Instead of putting 10 or 100 out into the environment, having to track them,and then when they die, collect them, you could put a thousand, a million, a billion robots into the environment. Just spread them around. You know that at the end of their lives, they’re going to degrade to nothing. You don’t need to worry about them. So that changes the way in which you think about robots and the way you deploy them.

Then the question is: Can you do this? Well, yes, we have shown that you can do this. You can make robots which are biodegradable. What’s really interesting is you can use household materials to make these biodegradable robots. I’ll show you some; you might be surprised. You can make a robot out of jelly. Instead of having a motor, which we have at the moment, you can make things called artificial muscles. Artificial muscles are smart materials, you apply electricity to them, and they contract, or they bend or they twist. They look like real muscles. So instead of having a motor, you have these artificial muscles. And you can make artificial muscles out of jelly. If you take some jelly and some salts, and do a bit of jiggery-pokery, you can make an artificial muscle.

We’ve also shown you can make the microbial fuel cell’s stomach out of paper. So you could make the whole robot out of biodegradable materials. You throw them out there, and they degrade to nothing.

Well, this is really, really exciting. It’s going to totally change the way in which we think about robots, but also it allows you to be really creative in the way in which you think about what you can do with these robots. I’ll give you an example. If you can use jelly to make a robot — now, we eat jelly, right? So, why not make something like this? A robot gummy bear. Here, I’ve got some I prepared earlier. There we go. I’ve got a packet — and I’ve got a lemon-flavored one. I’ll take this gummy bear — he’s not robotic, OK?We have to pretend. And what you do with one of these is you put it in your mouth — the lemon’s quite nice. Try not to chew it too much, it’s a robot, it may not like it. And then you swallow it. And then it goes into your stomach. And when it’s inside your stomach, it moves, it thinks, it twists, it bends, it does something. It could go further down into your intestines, find out whether you’ve got some ulcer or cancer, maybe do an injection, something like that. You know that once it’s done its job of work, it could be consumed by your stomach, or if you don’t want that, it could go straight through you, into the toilet,and be degraded safely in the environment. So this changes the way, again, in which we think about robots.

So, we started off looking at robots that would eat pollution, and then we’re looking at robots which we can eat. I hope this gives you some idea of the kinds of things we can do with future robots.”

Who is Jonathan Rossiter?

Jonathan Rossiter is Professor of Robotics at University of Bristol, and heads the Soft Robotics Group at Bristol Robotics Laboratory. His group researches soft robotics: robots and machines that go beyond conventional rigid and motorized technologies into the world of smart materials, reactive polymers biomimetics and compliant structures. Because they’re soft, these robots are inherently safe for interaction with the human body and with the natural environment. They can be used to deliver new healthcare treatments, wearable and assistance devices, and human-interface technologies. They wide impact from furniture to fashion and from space systems to environmental cleanup. They can even be made biodegradable and edible.

Currently a major focus of Rossiter’s work is on the development of soft robotic replacement organs for cancer and trauma sufferers and on smart “trousers” to help older people stay mobile for longer.