A captivating conversation is taking place about the future of artificial intelligence and what it will/should mean for humanity. There are fascinating controversies where the world’s leading experts disagree, such as: AI’s future impact on the job market; if/when human-level AI will be developed; whether this will lead to an intelligence explosion; and whether this is something we should welcome or fear. But there are also many examples of of boring pseudo-controversies caused by people misunderstanding and talking past each other. To help ourselves focus on the interesting controversies and open questions — and not on the misunderstandings — let’s clear up some of the most common myths.

TIMELINE MYTHS

The first myth regards the timeline: how long will it take until machines greatly supersede human-level intelligence? A common misconception is that we know the answer with great certainly.

One popular myth is that we know we’ll get superhuman AI this century. In fact, history is full of technological over-hyping. Where are those fusion power plants and flying cars we were promised we’d have by now? AI has also been repeatedly over-hyped in the past, even by some of the founders of the field. For example, John McCarthy (who coined the term “artificial intelligence”), Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester and Claude Shannon wrote this overly optimistic forecast about what could be accomplished during two months with stone-age computers: “We propose that a 2 month, 10 man study of artificial intelligence be carried out during the summer of 1956 at Dartmouth College […] An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves. We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer.”

On the other hand, a popular counter-myth is that we know we won’t get superhuman AI this century. Researchers have made a wide range of estimates for how far we are from superhuman AI, but we certainly can’t say with great confidence that the probability is zero this century, given the dismal track record of such techno-skeptic predictions. For example, Ernest Rutherford, arguably the greatest nuclear physicist of his time, said in 1933 — less than 24 hours before Szilard’s invention of the nuclear chain reaction — that nuclear energy was “moonshine.” And Astronomer Royal Richard Woolley called interplanetary travel “utter bilge” in 1956. The most extreme form of this myth is that superhuman AI will never arrive because it’s physically impossible. However, physicists know that a brain consists of quarks and electrons arranged to act as a powerful computer, and that there’s no law of physics preventing us from building even more intelligent quark blobs.

There have been a number of surveys asking AI researchers how many years from now they think we’ll have human-level AI with at least 50% probability. All these surveys have the same conclusion: the world’s leading experts disagree, so we simply don’t know. For example, in such a poll of the AI researchers at the 2015 Puerto Rico AI conference, the average (median) answer was by year 2045, but some researchers guessed hundreds of years or more.

There’s also a related myth that people who worry about AI think it’s only a few years away. In fact, most people on record worrying about superhuman AI guess it’s still at least decades away. But they argue that as long as we’re not 100% sure that it won’t happen this century, it’s smart to start safety research now to prepare for the eventuality. Many of the safety problems associated with human-level AI are so hard that they may take decades to solve. So it’s prudent to start researching them now rather than the night before some programmers drinking Red Bull decide to switch one on.

CONTROVERSY MYTHS

Another common misconception is that the only people harboring concerns about AI and advocating AI safety research are luddites who don’t know much about AI. When Stuart Russell, author of the standard AI textbook, mentioned this during his Puerto Rico talk, the audience laughed loudly. A related misconception is that supporting AI safety research is hugely controversial. In fact, to support a modest investment in AI safety research, people don’t need to be convinced that risks are high, merely non-negligible — just as a modest investment in home insurance is justified by a non-negligible probability of the home burning down.

It may be that media have made the AI safety debate seem more controversial than it really is. After all, fear sells, and articles using out-of-context quotes to proclaim imminent doom can generate more clicks than nuanced and balanced ones. As a result, two people who only know about each other’s positions from media quotes are likely to think they disagree more than they really do. For example, a techno-skeptic who only read about Bill Gates’s position in a British tabloid may mistakenly think Gates believes superintelligence to be imminent. Similarly, someone in the beneficial-AI movement who knows nothing about Andrew Ng’s position except his quote about overpopulation on Mars may mistakenly think he doesn’t care about AI safety, whereas in fact, he does. The crux is simply that because Ng’s timeline estimates are longer, he naturally tends to prioritize short-term AI challenges over long-term ones.

MYTHS ABOUT THE RISKS OF SUPERHUMAN AI

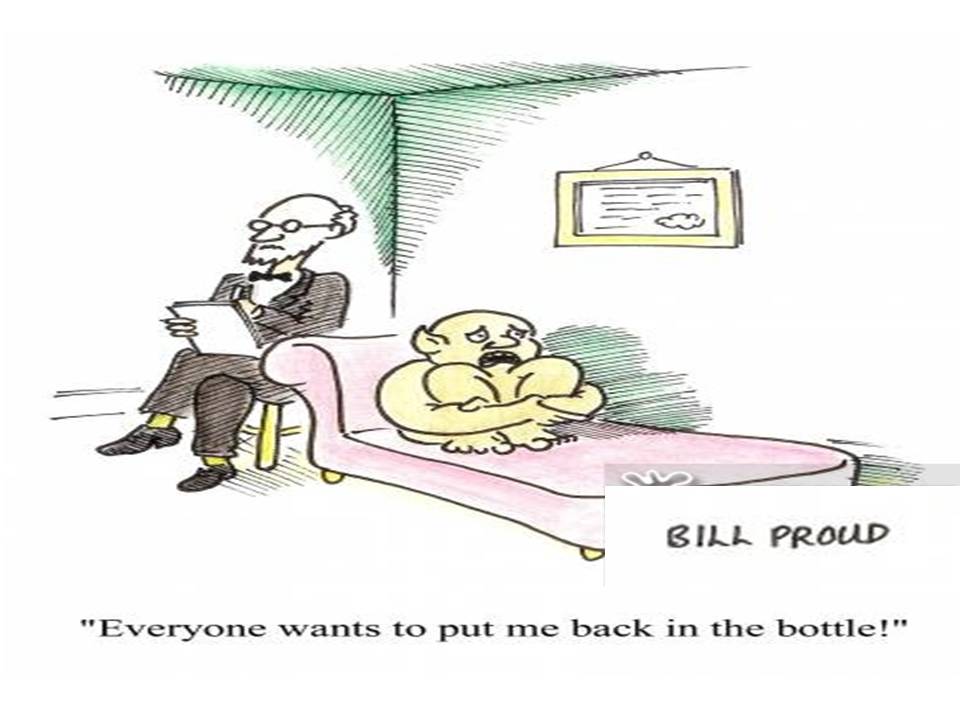

Many AI researchers roll their eyes when seeing this headline: “Stephen Hawking warns that rise of robots may be disastrous for mankind.” And as many have lost count of how many similar articles they’ve seen. Typically, these articles are accompanied by an evil-looking robot carrying a weapon, and they suggest we should worry about robots rising up and killing us because they’ve become conscious and/or evil. On a lighter note, such articles are actually rather impressive, because they succinctly summarize the scenario that AI researchers don’t worry about. That scenario combines as many as three separate misconceptions: concern about consciousness, evil, and robots.

If you drive down the road, you have a subjective experience of colors, sounds, etc. But does a self-driving car have a subjective experience? Does it feel like anything at all to be a self-driving car? Although this mystery of consciousness is interesting in its own right, it’s irrelevant to AI risk. If you get struck by a driverless car, it makes no difference to you whether it subjectively feels conscious. In the same way, what will affect us humans is what superintelligent AI does, not how it subjectively feels.

The fear of machines turning evil is another red herring. The real worry isn’t malevolence, but competence. A superintelligent AI is by definition very good at attaining its goals, whatever they may be, so we need to ensure that its goals are aligned with ours. Humans don’t generally hate ants, but we’re more intelligent than they are – so if we want to build a hydroelectric dam and there’s an anthill there, too bad for the ants. The beneficial-AI movement wants to avoid placing humanity in the position of those ants.

The consciousness misconception is related to the myth that machines can’t have goals. Machines can obviously have goals in the narrow sense of exhibiting goal-oriented behavior: the behavior of a heat-seeking missile is most economically explained as a goal to hit a target. If you feel threatened by a machine whose goals are misaligned with yours, then it is precisely its goals in this narrow sense that troubles you, not whether the machine is conscious and experiences a sense of purpose. If that heat-seeking missile were chasing you, you probably wouldn’t exclaim: “I’m not worried, because machines can’t have goals!”

I sympathize with Rodney Brooks and other robotics pioneers who feel unfairly demonized by scaremongering tabloids, because some journalists seem obsessively fixated on robots and adorn many of their articles with evil-looking metal monsters with red shiny eyes. In fact, the main concern of the beneficial-AI movement isn’t with robots but with intelligence itself: specifically, intelligence whose goals are misaligned with ours. To cause us trouble, such misaligned superhuman intelligence needs no robotic body, merely an internet connection – this may enable outsmarting financial markets, out-inventing human researchers, out-manipulating human leaders, and developing weapons we cannot even understand. Even if building robots were physically impossible, a super-intelligent and super-wealthy AI could easily pay or manipulate many humans to unwittingly do its bidding.

The robot misconception is related to the myth that machines can’t control humans. Intelligence enables control: humans control tigers not because we are stronger, but because we are smarter. This means that if we cede our position as smartest on our planet, it’s possible that we might also cede control.

Source: https://futureoflife.org/