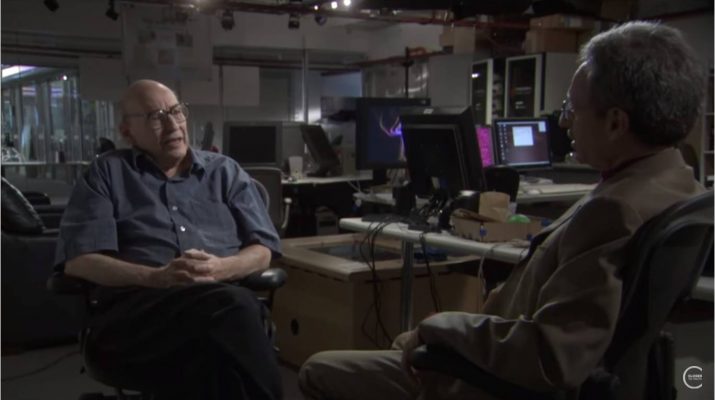

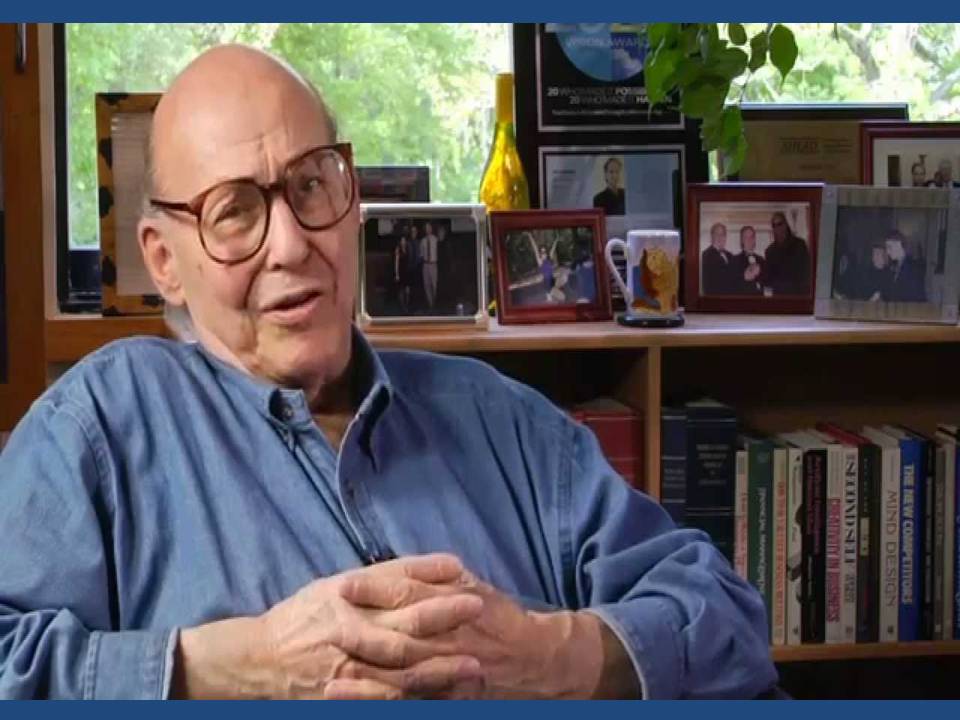

One of AI’s legendary pioneers, Marvin Minsky, co-founder of what is now the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and considered to be the “father of AI,” is explaining why consciousness is so mysterious.

How can the mindless microscopic particles that compose our brains ‘experience’ the setting sun, the Mozart Requiem, and romantic love?

How can sparks of brain electricity and flows of brain chemicals literally be these felt experiences or be ‘about’ things that have external meaning? How can consciousness be explained?

Marvin Minsky, who combined a scientist’s thirst for knowledge with a philosopher’s quest for truth as a pioneering explorer of artificial intelligence, helped inspire the creation of the personal computer and the Internet.

Marvin Minsky has made many contributions to AI, cognitive psychology, mathematics, computational linguistics, robotics, and optics. In recent years he has worked chiefly on imparting to machines the human capacity for commonsense reasoning. His conception of human intellectual structure and function is presented in two books: The Emotion Machine and The Society of Mind (which is also the title of the course he teaches at MIT).

He received the BA and PhD in mathematics at Harvard (1950) and Princeton (1954). In 1951 he built the SNARC, the first neural network simulator. His other inventions include mechanical arms, hands and other robotic devices, the Confocal Scanning Microscope, the “Muse” synthesizer for musical variations (with E. Fredkin), and one of the first LOGO “turtles”. A member of the NAS, NAE and Argentine NAS, he has received the ACM Turing Award, the MIT Killian Award, the Japan Prize, the IJCAI Research Excellence Award, the Rank Prize and the Robert Wood Prize for Optoelectronics, and the Benjamin Franklin Medal.

The body works on the laws of physilogy, a subset of the laws of physics. The mind creates an awareness of the outside world through the 6 senses, 1 vision, 2 hearing, 3 taste, 4 smell, 5 smell, 6 selfawareness, i.e. feeling hunger, fullness, pain etc. Some people are independent of others, emphatheic, and some fall for the sympathy for others take on their feelings in “love”.

“there is no inner voice” explains “How can consciousness be explained?”

Theorem:

There is actually only a monologue, called the mind, within the outside world. There never was an inner monologue produced by the brain. That is why thinking feels effortless.

Proof:

The sense of agency (i.e., I am the author of my actions) is not possible because as physical matter and energy our bodies move authored by the laws of physics, not “I”, and not by our own subjective thoughts and intentions. Therefore, the sense of mind ownership (i.e., my inner monologue belongs to me) is also not possible.

Is that a bit like Leonardo dissecting the body to find the soul?

yes, that is exactly what the OP discusses when it asks “How can sparks of brain electricity and flows of brain chemicals literally be these felt experiences or be ‘about’ things that have external meaning?”

What we call vision or seeing an object is an example of subjective experience or qualia. However, an equivalent definition of seeing is knowing how an object subtends space in vivid detail. Furthermore, knowledge independent of vantage or viewpoint is even more awareness than vision provides. Hence, the ecosystem which builds large animals and trees from point like seeds is where awareness occurs, and does not occur within each scientist trying to perceive how things work by looking at the ecosystem through a microscope.

First we read “particles that compose our brains”, and then the question follows “How can consciousness be explained?”. So, what first phrase has to do with the later question? If we aim to explain the mechanisms of consciousness we have to leave the brain with its particles alone.